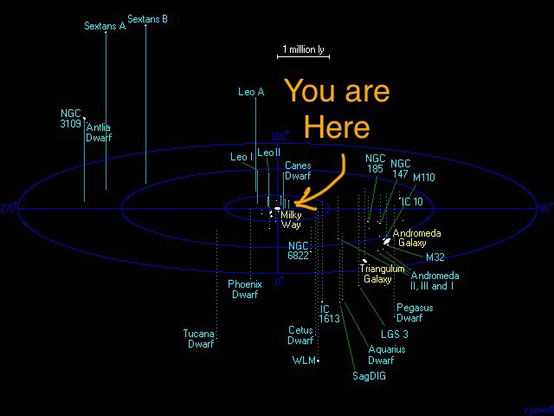

Edwin Hubble announced #OTD in 1925 that Andromeda and other spiral nebulae were in fact separate galaxies outside the Milky Way, in a paper read to an AAS meeting by H.N. Russell.

The Universe was far larger than what many astronomers had allowed themselves to imagine. It was more than just our little island of stars.

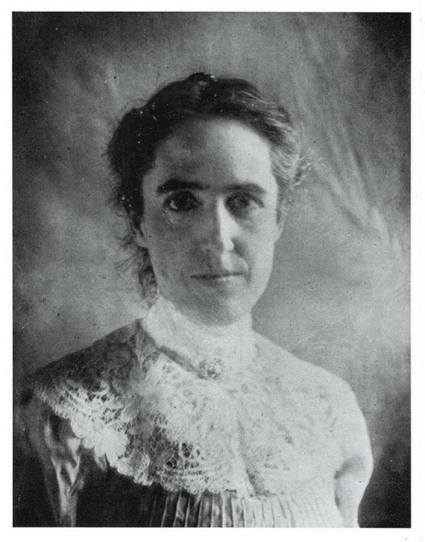

Hubble built on observations by Vesto Slipher, collaborated with Milton Humason, and relied on Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s Cepheid variable work to reach this conclusion.

It seems hard to believe, but there are people alive today who were born into what scientists thought was a much smaller universe.

Former US President Jimmy Carter was three months old when Hubble made his announcement.

Betty White, who passed away just a few years ago, was always my favorite example of this. She was about to turn three years old when we realized there are other galaxies.

Hubble’s announcement — Other galaxies exist! Our Milky Way is just one in a Universe full of them! — was made on the third day of the 33rd Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, in a paper read by H.N. Russell. The meeting started on December 30th; I don’t know if Hubble waited for New Year’s Day to be dramatic.

For astronomers, the announcement probably wasn’t a sudden revelation. Hubble had been discussing this result with colleagues, and word had gotten around.

It’s hard to imagine the pre-Hubble view of the Universe, though it was less than 100 years ago.

Just a year before Hubble’s announcement, many astronomers thought the collection of stars that make up our galaxy was Everything.

Astronomer Harlow Shapley was perhaps the leading proponent of the establishment view. He had long argued that spiral nebulae seen by astronomers — shapes any kid would now recognize as galaxies — were just dust clouds inside the Milky Way.

Images: Huntington Library

But there had always been astronomers who suspected that the Milky Way was just one of many galaxies. This view goes at least as far back as Immanuel Kant’s “Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens,” which he published anonymously in 1755.

It was the identification of Cepheid variable stars in M31 and other spiral nebulae that allowed Hubble to prove they were so far away that they must be outside the Milky Way.

A Cepheid variable is a type of star whose brightness waxes and wanes over a period of time that tightly correlates with its maximum brightness.

Measure that period and you know its absolute brightness. Compare that to how bright it appears, and you can estimate its distance.

This important property of Cepheid variable stars was discovered by astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt. It makes them “standard candles” (a term she coined) that we can reliably use for establishing distances to cosmologically nearby galaxies.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s period-luminosity relationship for Cepheids is one of the first rungs on the “cosmic distance ladder,” the collection of methods used by astronomers to measure extragalactic distances.

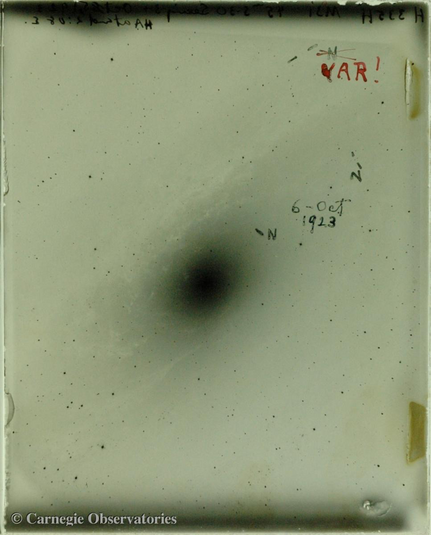

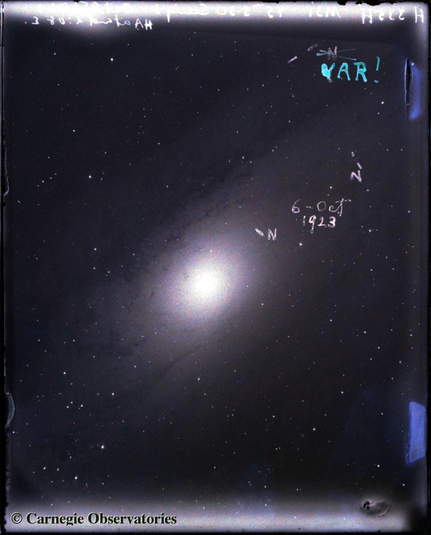

In the early morning hours of October 6, 1923, Edwin Hubble took a photo plate of M31 showing a Cepheid variable star. He originally mistook it for a nova - you can see where he has crossed out an “N” on the plate and excitedly replaced it with “VAR!”

Applying Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s period-luminosity relationship to subsequent observations, Hubble concluded that the distance to M31 was greater than reliable size estimates for the Milky Way.

Image: Carnegie Observatories

Hubble kept Shapley in the loop as he built the case for separate galaxies throughout 1924, alerting him to the discovery of Cepheid variables in M31, M33, and other spiral nebulae.

Shapley, who had long argued that the Milky Way was the whole Universe, doubted Hubble at first. But he eventually relented in the face of growing evidence.

Upon receiving one of Hubble's letters, Shapley remarked to doctoral student Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin “Here is the letter that destroyed my universe.”

Astronomically, January 1st is a meaningless date. It is an arbitrary reference point in a system based on the approximate orbital period of an otherwise unremarkable star that is perhaps only notable for having a life-bearing planet.

But for those of us who reckon time by this system, today is the 99th anniversary of humanity taking a monumental step towards understanding our place in a Universe that is vast and puzzling, but ultimately knowable.

Happy New Year!

Image: Richard Powell

@mcnees Hey, our star has above average metallicity, have a little respect!

@mcnees happy new year!

@mcnees A very good point. Happy New Year nonetheless!

@jeanoappleseed Happy new year!

@mcnees There's a good play about this, "Silent Sky" by Lauren Gunderson.

@nazgul @mcnees @Wraithe I'm not seeing that in early _Skylark_ / _Lensman_ novels - EES does use "Island Universe" occasionally for "Galaxy" and sometimes "superuniverse", but even in _First Lensman_ writes

"The Galactic Patrol became for him an actuality; a force for good pervading all the worlds of all the galaxies of all the universes of all existing space-time continual."

Neither is used as a concrete noun in the first _Skylark_, though I don't have the original (edit: 1921) edition.

@oddhack @nazgul @mcnees The early Skylark does use that model, but then he (EE) moves to the galactic model, aka, the greatest power creep until “Rise of Skywalker” wherein Seaton (with assists) destroys a galaxy (sorry about the spoilers for an almost 100 year old series )

The move to the galactic model is pretty seamless ie: he just doesn’t mention galaxies until he does.

@mcnees I think about analogs of this from my own life all the time. “When I was a kid astronomy et al.” We didn’t know if black holes were really real or have evidence of exoplanets. Dinosaur extinction and space, how could there be a connection? That sort of thing.

@mcnees

My mother was born in May of 1925 and is still chugging along.

We are quite proud of our cousin. He did that remarkable work at the observatory on Mt. Wilson.

@mcnees my astronomer father, in his 90s, likes to pretend he’s explaining general relativity and fast living when he says “the universe was seven billion years old when I was in elementary school, now it’s thirteen.“

@mcnees We don't know if the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct—and may never know—but if it is, the universe is immensely larger still.

@mcnees It’s astounding how much of a change in perspective that is. Our view of the universe suddenly became much more immense.